|- WJM home -|

Preface I, William J. Martin, WJM Architect, formally developed my architectural design philosophy concepts as expressed here, in 1991, just prior to the launch of the Architectural firm. These ideas have been influenced by my education in the U.S. at Carnegie-Mellon and at Pratt Institute, as well as architectural and art history, studies of economic concepts, observations of the attitudes and emotions of non-design persons, and the practical real world knowledge gained by being directly involved in the design of actual constructed buildings of all types.

I wanted to become an architect to help people. People need well designed shelter for themselves, families, businesses and all type of endeavour that requires sheltered space. Architecture has the power to create beautifully effective shelter for the needs, hopes, dreams and memories of humankind, both collectively and individually.

This design philosophy is an attempt to reconcile and bring design factors into an equilibrium, and create a NEW sustainable "architectural gestalt" [6], to transcend architectural fashion. A treatise to explain and understand why it is necessary to intellectually balance design factors empowering all architects and designers to create a built environment that transcends the sum of its individual parts. It is assumed that academics and students will respect this work as a statement of a unique philosophical point of view. Like all points of view, it is directly reflective of the context in which it was developed and is personal to the author. Phrases in quotes not attributed to a source are phrases coined by William J. Martin to describe this philosophical architectural point of view. Therefore it is requested that if colleagues, academics or students use any portions or excerpts of this work, including coined terms and phrases, that proper credit be given to William J. Martin, Architect.

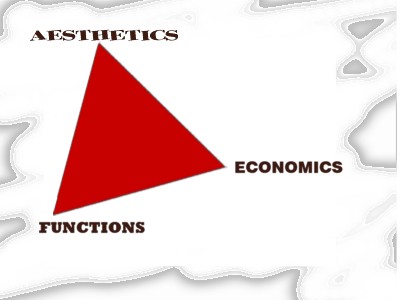

Finding the Equilibrium of "Appropriate Balance" between design factors requires Architecture and Building Design be recognized as a Socio-economic Artform. Architecture and Building Design should serve the people that utilize, not those who design. Does architectural design imply aesthetic principles are inherent? Since architectural design arranges objects in spatial locations and considers their relationship to eachother and persons, aesthetic [5][6] principles are inherent and are applied whether or not they have been considered by the designer. Aesthetic principles exist in any building design and cannot be separated from the design, therefore making them inherent. Aesthetics is a fundamental design factor. Does architectural design imply purpose? Designing by definition implies it is done for some purpose [6]. Purpose implies the design is created to perform some desired function [5]. The term function as meant here, refers to the purpose of the entire function and sub-functions. The Functions cannot be separated from the design. Functions is a fundamental design factor. Does architectural design imply a real space? A real building design occupies, or will occupy a real space. Real three-dimensional space… length, width, and height are fundamental to the design of real buildings. Real materials… earth, wood, steel, concrete, plastic are fundamental to making the architectural design into a physically real building. In order for a building design to become a real building, you must build the building.

The process of building involves human manpower and building materials. The industries that produce the materials are economic entities that, for a price, will produce the materials needed for the building construction. Human manpower is a socio-economic entity that, for a price will construct the building from the materials. When I use the word “price”, I mean at some economic cost to the society engaged in constructing the building.

The economics of building also has a socio-political facet. Buildings are regulated by laws that create limitations, social expectations, and requirements on the building for a presumed general benefit. In many past societies, religion and politics dominated building design in this manner (example: cathedrals of Europe). These aspects of building a real design are encompassed in the social science of Economics.

Environmental impact and green design sustainability are assessed through economic analysis.

Economics is by definition a social science concerned with analysis of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services [6] AND the thrifty and efficient use of material resources [5]. The process of obtaining and placing building materials, by utilizing or transforming natural resources by man and machine, is an economic and social endeavor. Therefore the architectural design of real spaces requires that the economic components be considered in the process of creating the design. Economics cannot be separated from the design of a real three-dimensional building. Economics is a fundamental design factor. These three factors represent the absolute minimum derivative constituent parts without which architecture would not be what it is. --THIS IS IMPORTANT--

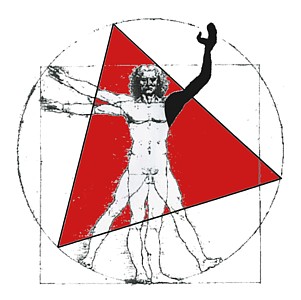

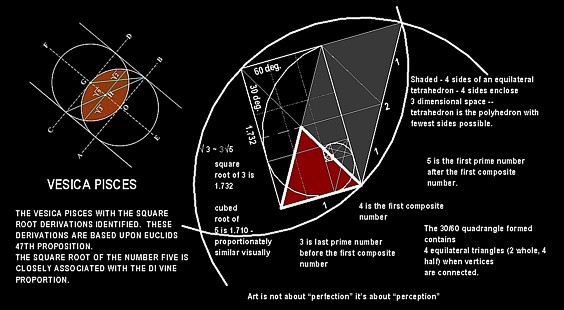

The Appropriate Triangular Balance between design factors results in higher design. Physically, the triangular shape is an inherently stable structural shape and provides an appropriately descriptive concept model for the balancing of the three factors.

The Equilibrium [6] of "Appropriate Balance" describes the state of intellectual balance between opposing design forces and actions that is deliberately designed to be in harmonious balance. The artistic balance created by design is theoretically in place for the entire life of the building. To me, it is the artistic soul of the building. I call this artistic soul "Econo-functional Aesthetic Balance" or E-FABism.

Economic theory describes a concept known as a “production possibilities frontier” [4]. This plainly stated is as follows: Assuming finite resources (human labor as well as natural resources), there exists a maximum possibility of producing goods and services. By evaluating and analyzing the use of material and labor resources, it is possible to determine the most efficient way of utilizing the finite resources. By studying how best to apply these finite resources, one can produce the maximum output by minimizing economic waste. The appropriate triangular balance that I describe is analogous to a production possibilities frontier. By considering the design factors as three parts of a whole, maximizing each factor, and striving to create a thoughtful balance between the factors, better design can theoretically be achieved by applying each factor in the most appropriate way. The designer seeks to maximize the "Econo-functional Aesthetic Balance"

Assuming the designer is given finite resources, finding the right balance between the factors will have a great impact on the success of the design. This is an entirely new way of thinking about the architectural design of buildings. Never before has an economic factor been embraced as a significant elemental component in the process of artistic architectural creation. Previously architects have tried to ignore an economic factor and have stubbornly refused to admit that an economic factor could play any meaningful creative role in the process of design. This stubborn denial has cost society and the architectural profession dearly. In the past few decades, frustrated clients have begun to turn away from architects and sought others to comment on matters of design. Design decisions that were once solely the architect's have been usurped by other related professions using economics and "value Engineering" to degrade the quality of the architect's design after the fact. This has led to a general degradation of the quality of our built environment. This would not happen if architects recognized, accepted, and included as fundamental the "Economic Factor" in the process of creating their building designs.

It is only natural for clients and building users to desire value in their buildings. Architects need to be creative and provide real recognizable value through the thoughtful design of all three factors. The value of aesthetics, balanced with the value of function, further balanced with value of minimizing economic waste needs to be clearly demonstrated to clients, building users and society.

"The greatest architectural creativity springs from respect for the factors that constrain the design."

Each factor, individually, represents one portion of a total theoretical design. All three factors are present in any design and no real building can exist without all three factors present in some manner. The designer’s objective should be to balance all three portions to achieve the maximum "Econo-functional Aesthetic Balance". When successfully balanced, the whole architectural design, with the equilibrium created, artistically exceeds the sum of its parts. It transcends itself and reaches a higher plane of artistic expression. From my observations of the built environment, I see many buildings suffer from either the: ---"Seduction of the Aesthetic", where the primary effort is put into creating the visual beauty of form, OR the ---"Obsession of cost control", where the primary effort is put into constructing as cheaply as possible, OR the ---"Compulsion of Efficient Function", where the primary effort is put into planning only the fundamental purpose of space. Focusing on any one or two factors without considering the third results in the design being theoretically unbalanced and falling short of its full potential to reach the maximum "Econo-functional Aesthetic Balance"

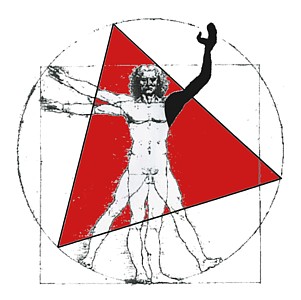

In the first century BCE, Roman Architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, also known as simply -- Vitruvius --authored his book De Architectura. This book is known today as The Ten Books on Architecture [1]. Vitruvius is famous for asserting in Book 1 Chapter 3, that a building must exhibit the three important qualities of firmitas, utilitas, venustas — often translated as firmness, commodity, and delight. That is, a building must be strong , useful, and beautiful.

This is also known as the Vitruvian Triad. Vitruvius had identified these three qualities, on which, good architecture would depend.

Vitruvian delight is concerned with the aesthetics of buildings. This corresponds to the Aesthetics factor as being fundamental to architecture.

Vitruvian commodity is concerned with the spatial layout presenting “no hindrance to use”. This roughly corresponds to spatial function, location and orientation of a building design. While this does correspond to the Functions Factor, it does not describe any balance between functions and sub-functions or balance with other factors.

Vitruvian firmness is concerned with solid foundations and the wise choice of building materials creating a firm structurally sound building.

Vitruvius describes the three important qualities but he does not describe the need to create balance between these qualities. There is no econo-functional aesthetic balance here since there is no expressed need to create balance in the Vitruvian Triad.

In Book 1, Chapter 2, and as a separate fundamental principle not included in the three, Vitruvius discusses 2 stages of economy. The translation from the latin states the first stage of economy is the “proper management of materials and of site, as well as a thrifty balancing of cost and common sense in the construction of works”.

Here again, Vitruvius describes the quality but he did not describe the need to create balance between qualities.

The second stage of economy is the planning for the various class divisions of Roman society.

The Roman classical style of architecture was largely borrowed from the Greeks and built throughout the Roman World with little regard for the needs of local subjugated populations. The conquering Romans were simply not sensitive to this. Imposing Roman order and control was their paramount concern.

The Equilibrium of "Appropriate Balance" seeks to create balance between Vitruvian qualities that is deliberately designed to be harmonious and create Econo-functional Aesthetic Balance.

Architect Louis Sullivan (1856-1924) said, Form Follows Function (F-F-F). With this statement, Sullivan tells us that he believes the architectural form of a building should follow the function of its underlying structure and purpose. His derivative F-F-F statement has been continuously mis-interpreted since he said it in 1896. It is many times used as justification for making the function of a building the primary consideration in it's design. Sullivan meant F-F-F in a more poetic way [2]. Like the way a persons skin is their outer appearance and covers the structure of the skull. The form of the skin follows the function of the shape of the skull and the two work together to create the expressive beauty of the person. The human face is capable of a great many expressions and so is the architectural design of buildings. Sullivan's style of lightness grew out of the availability of new construction materials. At that time, iron and steel structures were not previously available to architects. Iron and steel structures did not require heavy solid exterior bearing walls. Tall building designs could now be light and full of windows. At the same time, Sullivan's exterior forms followed the function of these new materials in a poetic skin over bone analogy. Sullivan's design breakthough was directly connected to the social and economic context of mining iron and making steel in the late nineteenth century United States. Sullivan's new approach to design would not have been possible outside of this economic context. The poetry of F-F-F does not acknowledge social and economic context as a factor in the creation and design of buildings. This has always made me feel a major fundamental component had been left out of Sullivan's F-F-F. "Appropriate Balance" demonstrates that Form Does NOT follow Function. Form and Function are given weight and should balance. However, this still fails to account for the Economic Factor.

Perhaps it should have been "Form Follows Function Follows Economics". Or in an "Appropriate Triangular Balance" possibly "Form Balances Function, Function Balances Economics, Economics Balances Form". Or as I have stated, "Econo-functional Aesthetic Balance" The great International Style Architect Mies Van der Rohe (1887-1969) said, "God is in the details." Anyone who has engaged in the serious design of real buildings knows, God is NOT in the details; the Devil resides in the details. Mies saw "God" in the inter-dependant relationship of a buildings elemental components. "Appropriate Balance" sees Mies's "God" in discovering the Appropriate Balance between the three design factors. God is the "Econo-functional Aesthetic Balance" Mies also said, Less is More. Despite the economic connotations of this statement, Mies, like Sullivan before him, meant this in a poetic aesthetic sense in creating the greatest effect with the least means. Deriving aesthetics from a buildings elemental components creates the beauty Mies describes with Less is More. This approach to architectural design can be somewhat restictive in that it limits how the aesthetic is derived. The introduction of a building component that was purely decorative and not elemental would be considered taboo by Mies.

From the viewpoint of E-FAB, Less is NOT More. Less is NOT a bore [3]. Less is less. "Less is More" is probably the single most destructive phrase to come out of the modernist architectural lexicon. The poetry of Mies was mis-interpreted and mis-used by building developers who used the phrase to justify stripping buildings of all significant meaning as objects of art in order to build as cheaply as possible.

It is historically unfortunate that breakthroughs in the mathematical understanding of economics emerged contemporaneously with the stylistic expression of modernism and "Less is More" became the perverse slogan of builders driven by greed. The impact of this continues today.

Less and More should never have been equated. Less and More should create a theoretical balance. Can More be achieved with a little less? This may tip the equilibrium out of balance. E-FAB strives to achieve the poetry of Less and More through appropriate balance between the two. Less balances More in a manner that retains significant meaning and the artistic soul of the building. The lesson of Less is More is that it should have been "Less balances More".

In a Time Magazine article June 14, 1954,[7] Mies is quoted as saying "The old way was to look at architecture as a display of forms. We concentrate on the simple, basic structure, and we believe the structural way gives more freedom and variety. Remember, we are not trying to please people. We are driving to the essence of things."

In the greater context of art and history, I understand. In physics, around this time, Einstein was working to derive an single equation to explain and unify sub-atomic and universal forces. After Einstein had shown us E=mc^2, there was a growing belief that everything could be reduced to a single equation; A simple, beautiful, theory of everything. In an artistic way, Mies was part of this movement and "driving to the essence of things."

However, from the viewpoint of E-FAB, pleasing people cannot be separated from achieving appropriate balance. It is at this point, in my thinking, that Mies ceases to be a true architect and crosses over into something that is more like sculpture than architecture. "Starchitecture" leaves me with this same impression.

It is possible to over-derive. To reduce something to less than it's minimum constituent parts. Reduction to a point where it is no longer itself. It may be aesthetic, but it is overall, less than it could be.

Later in the same article, Mies says Architecture is great "only when it is an expression of its time. Architecture is the battleground. It is a struggle to find the essential factors."

On this, E-FABism is in agreement.

The architectural style that results from “E-FAB” does not fit into a single set of defined aesthetic principles. It is not Modernism, Post-Modernism, Classical or Colonial. It is "E-FABism" E-FAB designs are intellectually aesthetic and directly reflect the client/ users needs. E-FAB designs are sensitive to local past, present and future cultural conditions. An E-FAB design created in the Philippines or India would not look like an E-fab design created in the U.S., however all three designs would share the underlying principles of E-FAB and would be appropriate in their respective settings. Respect for local building methods, new technologies and materials, as well as local cultural, religious and economic factors would be present in all three designs.

The “style” results from local indigionous architectural concepts being re-defined and re-invented using E-FAB principles. The resulting style can be described as “Vernacular E-FAB” and fits seamlessly and harmoniously into its setting, whether urban, suburban or rural in nature. The beauty of this kind of style flows poetically from the "Appropriate Balance" intelligently created through E-FAB principles.

Style is no longer only about the aesthetics remaining when the building is completed, it is now a far more profound and higher expression of human creation. The principles used to create the design are intellectually retained in the poetic vernacular expression of the architecture for the life of the building. To me this is the very soul and the art of architecture.

The Vernacular E-FAB Architectural Style and EFAB-ism is a completely new way to think about architectural aesthetics and style.

Many indigionous building methods have qualities that are environmentally sensitive. Many come from renewable source material, and allow for reduced energy consumption. In the Southwest United States indigionous buildings utilize adobe bricks as a building material. The adobe brick has heat retention and dispersion qualities that take advantage of the natural energy flows of the local climactic condition. Made from locally sourced materials, adobe is a renewable and re-usable resource. This makes adobe an ideal building material from the viewpoint of green design since the materials have a lower impact on the environment and the building will need less energy to maintain comfort.

This is just one example, but it illustrates the point of how E-FAB principles applied to local indigionous architecture can have a profound impact. Balancing the latest technology with indigionous design of renewable local materials achieves both E-FAB and Green Design. Well designed buildings can be built using environmentally responsible localized construction materials and methods. The green design movement is Econo-functional Aesthetic Balance. Vernacular E-FAB is green.

Application of this philosophy is demonstrated by the "Blind Design Paradox". This example begins with deliberately reducing the aesthetic factor to visual aesthetics to make a point. The paradox is useful since many people tend to think of aesthetics as derived only from visual beauty. Designing for the visually impaired has obvious implications for the aesthetic factor. Designing a successful object or building is, in many cases, heavily dependent upon visual aesthetic. The Paradox of a designed building not needing a visual aesthetic, highlights the concept of "Appropriate Balance". The visually impaired building user is unable to appreciate the visual aesthetic and beauty in a visual aesthetic design factor. Focusing in on creating only visual beauty of form in this situation is not appropriate and is theoretically not relevant from the perspective of the building user. By separating the visual aesthetics from the other two factors, the "Blind Design Paradox" takes the focus off of the visual beauty of design and highlights the important role of balancing all three factors. Visual aesthetics alone does NOT constitute good design. The underlying point of this example demonstrates the role of the "Equilibrium of Appropriate Balance" when all three factors in the design interact. In the "Blind Design Paradox", the "Appropriate Balance" between the factors is achieved not through visual beauty, but through the textural and acoustic design of architectural elements. In fact, the space could be visually unaesthetic, poorly proportioned, and devoid of any light or color. These normally important aspects of design are theoretically not important to a visually impaired building user since they cannot be visually perceived. The visually impaired building user appreciates the beauty, not visually, but through the textures and acoustics of architectural elements while utilizing the function of the spaces designed for them. The "Aesthetics Factor" is affected by refining it as the beauty of the physical texture and acoustical properties of the materials selected by the designer to create the aesthetic and balance the functional and economic requirements. In this example the primary effort is not put into creating the visual beauty of form. This factor utilizes tactile and acoustic beauty to create the aesthetics of the design. The "Functions Factor" is affected by the design of space that needs to make use of material textures not visual material appearance. An example of this is flooring texture to communicate room type and function, wall textures to assist users in locating and orienting themselves, and even acoustic cues designed into the building. This factor considers the functional purpose of the building to make it perform for the visually impaired building user and balance with the aesthetic and economic factors. The "Economics Factor" is affected by the re-allocating of economic resources to obtain the appropriate diversity of textured materials and acoustic cues necessary to realize the design and accomplish a balance with the function and aesthetic factors. This factor considers the reasonable availability of these materials or whether new materials or technologies will need to be developed. This should also reasonably consider the economic means of the user as defined by the resources allocated to accomplish the construction of the design. It is important to understand that even in this theoretical example, the Formal Aesthetic Factor is not eliminated or even decreased in importance. It has shifted from visual beauty to tactile and acoustic beauty and still must be balanced with the other factors to achieve equilibrium and maximize the "Econo-functional Aesthetic Balance". If the Three Factors are appropriately balanced the equilibrium created will transcend the sum of its parts. This creates architectural beauty that is far more profound. There are existing examples that demonstrate the less than pleasing effect of design that has NOT reached its full potential in our built environment. These examples include: --Casino Hotel designs that over-emphasizes the aesthetic factor. Function and economic factors are overwhelmed by the desire to carry out a design theme stolen from past historical architecture and inappropriatly embellished with glitz.. I suppose it could be argued that if you put many of these casino hotel designs in one place, it becomes contextually appropriate. However in the broader historical context, these buildings will probably be quickly demolished should they fail as businesses. --Overall roadway design that over-emphasizes the function factor. Aesthetic and economic factors are overwhelmed by the desire to connect every "point A" to every "point B" with asphalt ribbons that cut and damage the landscape, separate and isolate people from eachother, and reduces our ability to renew economic resources and encourages the wasting of existing economic resources. --Utility poles and overhead wires for electric power distribution over-emphasize the economic factor. Aesthetic and function factors are overwhelmed by the economic desire to distribute electric power to as wide an area as possible via ugly brown poles and a wiring system that has a 30% transmission loss. Applying E-FAB to existing buildings helps to understand the design of a building and how well it balances the three factors. A real building example of the "Equilibrium of Appropriate Balance" between factors is the Empire State Building in New York City. The Empire State Building is an excellent illustation of achieving "Appropriate Balance" in design.

This building was aesthetically well proportioned for the context of New York City, therefore maximizing the aesthetic factor. The building functioned well for it’s intended purpose, therefore maximizing the function factor.

Constructed as a real estate syndication during the Great Depression, the building reflected the economic context of its creation, therefore maximizing the economic factor.

Completed in 1931, the building design factors even now continue to be appropriately balanced. This, in my opinion, is the mark of a great architecture that transcends and becomes a higher form of artistic expression. When the transmission antenna was added years later, the building gracefully accepted it as if it was always meant to be part of the design. This added aesthetically and rebalanced the aesthetic factor beautifully. The building fulfilled a greater purpose functioning to an even higher degree and rebalancing the function factor. The economic affect of the antenna enhanced the value of the building and rebalanced the economic factor to the benefit of society. The poetry of the appropriate balance of the Empire State Building inspires me continuously. As shown above, Appropriate Balance principles can be applied to evaluate the success of existing building designs.

The World Trade Center Twin Towers The Freedom Tower The Great Pyramids of Egypt The Great Wall of China Cathedrals of Europe Fallingwater St. Peters in the Vatican Pyramids of the Maya Civilization As shown above, Econo-Functional Aesthetic Balance principles can be applied to evaluate the success of existing building designs. How well some existing buildings "balance" will be discussed here in the future. Some balance better than others. My hope is that architects will come to understand the importance of creating an Equilibrium of Appropriate Balance. This will lead to a better understanding of the value of an architect's design. When someone other than the architect decides to modify a building design through value engineering, the whole design suffers when parts are excluded or deleted from the design with no artistic consideration given to the impact on the whole design. This leaves the client and building users with "half a design". In the end it will not be the "value engineer" but the architect who will receive the criticism for an unbalanced design.

[2] H. W. Janson, 1977, "History of Art", 2nd Edition, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ USA, and Harry N. Abrams, inc., NY, NY, USA, pp 703

[3] Paul Heyer, 1993, "American Architecture", Ideas and Ideologies in the Late Twentieth Century, Van Nostrand Reinhold, NY, USA, pp 16

[4] Baumol and Blinder, 1982, "Economics", Principles and Policy 2nd Edition, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., NY, USA, pp 430-433

[5] Ching, 1995, A Visual Dictionary of Architecture, Van Nostrand Reinhold, NY, USA Aesthetics-- The branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of art, beauty, and taste, with a view to establishing the meaning and validity of critical judgments concerning works of art. Design--The creation and organization of formal elements in a work of art. Economics-- Careful, thrifty, and efficient use and management of resources. Function-- The natural or proper action for which something is designed, used, or exists. Aesthetics-- Appreciative of, responsive to, or zealous about what is pleasurable to the senses. Design-- To create, fashion, execute, or construct according to a plan. To devise for a specific function or end. Gestalt-- A structure, configuration, or pattern of physical, biological, or psychological phenomena so integrated as to constitute a functional unit with properties not derivable by summation of its parts. Economics-- A social science concerned chiefly with description and analysis of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services AND Thrifty and efficient use of material resources. Equilibrium-- A state of intellectual or emotional balance. OR a state of balance between opposing forces or actions that is either static or dynamic. Function-- The action for which a person or thing is specially fitted or used, or for which a thing exists: purpose.

[7] Time, June 14,1954, "Less is More", Time Magazine, Inc., NY, USA

Architectural Philosophy...

The Equilibrium of Appropriate Balance and

Econo-Functional Aesthetic Balance (E-FABism)

Design Factors

The Three Fundamental Factors of Architectural Design

E-FAB Man - part Vitruvian Man, part Modular Man and more, blended into E-FAB balanceE-FAB compared to the conventional wisdom of the past

E-FAB and Style

E-FAB and Green Design

The Blind Design Paradox

Examples of unbalanced design

Example of balanced design

Conclusion

References--

[1] Vitruvius, 1st Century BCE "The Ten Books on Architecture"

Feel free to email comments to comments@wjmarchitect.com.

Click here to return to the Main WJM Page